What is Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome? (Diagnosis and Treatment)

Very obese children and adults who have daytime fatigue and difficulty concentrating may be suffering from obstructive sleep apnea but in up to 20% of cases, the diagnosis may be even more serious. Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome, or OHS, is a sleep-related respiratory problem that can cause serious and in some cases irreversible damage to the body, greatly increasing mortality risk over a fairly short period of time.

The key to managing this condition is knowing how to spot it early.

What Is Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome (OHS)?

OHS, sometimes referred to as hypercapnic sleep apnea or Pickwickian Syndrome , is form of sleep-disordered breathing. Its characterized by the following:

- Patients are seriously overweight ( obese ), with a BMI greater than 30.

- They have a higher-than-normal amount of carbon dioxide, or CO2, in the bloodstream (a condition called hypercapnia ). This hypercapnia is present during the daytime but gets worse during sleep, sometimes leading to severe oxygen deprivation in the arterial blood supply.

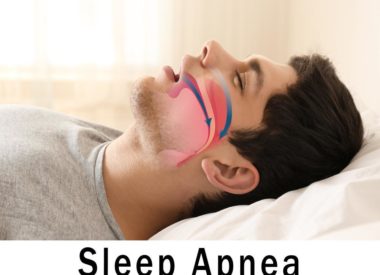

- This hypercapnia is caused by hypoventilation , or respiratory depression: episodes of shallow breathing or slower-than-normal breathing that are not caused by a lung disease, a neurologic disorder, or muscle weakness. People with OHS tend to hypoventilate more during REM sleep than in non-REM sleep. Sometimes their breath ceases altogether (similar to an apnea event).

This disease is associated exclusively with obesity. About 90% of patients diagnosed with OHS also have Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA).

OHS is dangerous because the high CO2 levels, combined with a lack of sufficient oxygen in the blood, can be a precursor to hypoxia or hypoxemia chronic, severe oxygen deprivation that causes tissue to deteriorate.

Over time, this deterioration leads to serious and even deadly emergencies like cardiopulmonary arrest (failure of the heart muscle) or respiratory failure.

How OHS Is Different from OSA

Although the two conditions are often closely related, they’re not the same, and they’re not always linked.

Some basic facts about OHS and OSA:

- About 8090% of the time, people with obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS) also have obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). However, researchers believe only about 1020% of people with obstructive sleep apnea also have OHS.

- While both OSA and OHS involve respiratory disruptions, these disruptions differ. If you have OSA, an obstruction of your upper airway will cause you to cease breathing many times per night (or even many times per hour). Typically, these apnea occurrences last a few seconds to a few minutes and wake you up with a gasp or choking sensation. After you return to sleep, you resume breathing normally until the next apnea occurs. During the day when you’re awake, however, you typically don’t experience such breathing irregularities.

- With OHS, you would experience long, continuous episodes of hypoventilation (shallow or slow breathing) while you sleep. These worsen in REM sleep. Unlike OSA, which affects you when you’re asleep, hypoventilation also occurs during the day when you’re awake. Whereas someone with OSA alone may have normal blood oxygen levels during the daytime, someone with OHS (or OHS and OSA) will have low blood oxygen levels and high CO2 levels both day and night.

OHS Symptoms

What does it feel like to have OHS? You may not notice any disruption to your sleep quality, particularly if you are not experiencing obstructive sleep apnea in addition to OHS.

However, you will likely experience some of the following:

- Concentration problems

- Difficulty exercising

- Excessive daytime sleepiness or fatigue

- Hyperactivity (in children)

- Prolonged nighttime sleep (though you are still tired after waking)

- Morning headaches

- Moodiness

- Memory problems

- Mouth breathing

- Nightmares

- Snoring

How OHS Is Diagnosed

OHS can be tricky to diagnose because its symptoms overlap with so many other conditions.

For example, its not uncommon for someone who’s very obese to feel tired, short of breath, or moody. People with OHS also frequently have other conditions like asthma or diabetes, which can present with some of the same problems.

If you have the known risk factors for OHS, in combination with the above symptoms, your physician may order lab tests to confirm a diagnosis.

Known OHS risk factors include:

- Clinical obesity

- Visible fat deposits around the chin and abdomen

- Swelling in the legs

- Thoracic kyphosis (forward curvature of the upper spine a hump)

- Facial or palate irregularities that might obstruct the upper airway

- Polyps, cysts, or other irregularities in the nasal passages

- Signs of right-sided heart failure

- A concavity of the chest a possible sign that the respiratory muscles have been overused while trying to overcome an obstruction

- The excessive use of drugs or alcohol, depressants, and certain medications like antihistamines

If your physician suspects OHS based on your medical history and the above risk factors, she may order the following tests to confirm a diagnosis.

- An arterial blood gas test to confirm daytime hypercapnia. You may have OHS if your carbon dioxide level is higher than 45 mm Hg.

- Echocardiogram to check for arrhythmias or damage to the ventricles of the heart (possible side effects of undetected OHS).

- Pulmonary function tests to show if you have an upper airway obstruction or a reduction in lung capacity or breathing efficiency.

- Chest radiograph (CXR) to look for deformities of the chest wall or signs of heart failure.

Your doctor may also check for an accumulation of blood or fluid in your tissue, higher-than-normal red blood cell count, high blood pressure in the lungs ( pulmonary artery hypertension ), and any signs of heart strain, enlargement, dysfunction, or right-sided heart failure.

In addition to these tests, your doctor may order an overnight polysomnography (sleep study) to check for hypoventilation, hypoxia and hypercapnia during sleep.

During the sleep study, sleep lab technicians can also conduct a nocturnal pulse oximetry to measure your heart rate and oxygen levels. Pulse oximetry can show whether you also have obstructive sleep apnea in addition to (or in lieu of) OHS.

Treatment of OHS

Currently, the treatment approach for OHS entails two steps:

- Losing weight. Obesity appears to be the main cause of OHS. To reverse or improve symptoms, you should try to return to a normal body weight with a healthy BMI. Some patients cannot achieve this goal with diet and exercise alone, especially if respiratory symptoms are too severe to allow for cardiovascular exercise. In those cases, bariatric surgery may be recommended.

- Complying with non-invasive ventilation (NIV), CPAP, or Bi-level PAP therapy . OHS patients without OSA may be given an NIV mask that provides assisted ventilation supplemented with oxygen. This treatment can help to normalize blood oxygen levels and prevent hypoxemia. In the case of OHS with OSA, CPAP or Bi-level PAP therapy may be more effective because the forced air pressure overcomes the soft tissue obstruction in the upper airway.

The bad news is, untreated OHS is very serious. In most cases, by the time it’s diagnosed, it’s already done enough damage to the heart and lungs to put you at a 23% risk of death over 18 months. That risk grows to 46% over 50 months.

The good news is, diagnosing and treating OHS with PAP therapy can improve or even normalize blood CO2 levels, bringing the mortality risk down to less than 10%.